The Shape of Losses: Midterms, Structural Floors, and the Limits of Waves

Direction Is Clear. Scale Is Not Unlimited

Midterm elections are designed to punish. From the earliest days of the modern republic, the party that holds the White House has faced the electorate’s corrective impulse two years into its term. This pattern is neither controversial nor new. What has changed, quietly but decisively, is not the direction of midterm outcomes, but their scale.

When the smoke clears after a bad midterm, governing parties no longer collapse into oblivion. Instead, they settle, again and again, near the same hard floor.

The Historical Floor

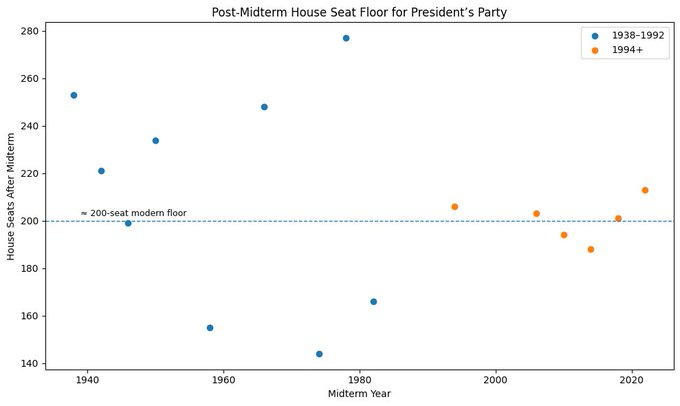

Looking across the postwar period, and especially the modern House, a clear pattern emerges. When the president’s party loses seats in a midterm, sometimes badly, it tends to bottom out at roughly the same place.

When we divide the data into two eras, the distinction is unmistakable:

1938–1992: the average post-midterm floor for the governing party is ~207 House seats

1994 onward: that average tightens to ~201 House seats

In the modern era, even severe midterm losses rarely push the president’s party much below ~200 seats, absent a true systemic shock. The Democratic losses of 2010 and 2014 represent the lower bound of that range. Conversely, Democrats emerged from 2022—despite an adverse environment—still holding 213 seats, reinforcing the same structural constraint from the opposite direction.

Losses are real. But they are no longer unbounded.

Why Scale Has Changed

The reason is structural, not political. The modern House is defined by:

Fewer marginal districts

Stronger partisan sorting

Reduced elasticity after redistricting

A larger share of seats that simply do not move

Midterms still swing against the president’s party. But they now do so within narrower rails.

This distinction, between direction and scale, is central to understanding 2026.

The 2026 Landscape

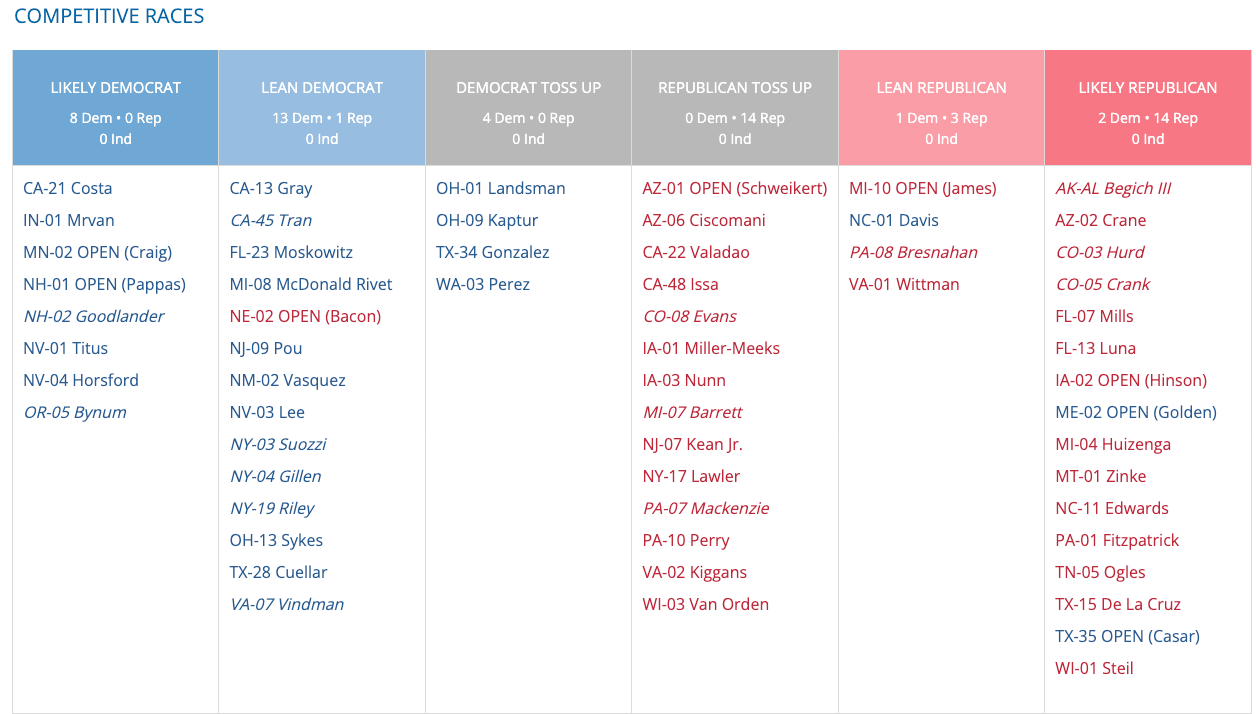

Republicans currently defend 218 House seats, including 14 of the 18 true toss-ups. That is not an overwhelming exposure by historical standards. It is, in fact, relatively light.

Our Presidential Exposure Model (PEM v2), built using the CARVER framework, points clearly to a “prepare for losses” environment. That conclusion aligns with fundamentals: presidential approval in the low 40s, historical midterm penalty, and a national mood that remains adverse to the governing party.

At the same time, our broader modeling—dating back to December—places the generic ballot roughly in the D+4 to D+5 range, establishing the direction of travel. Republicans are under pressure. That much is clear.

What remains less discussed is how far that pressure can realistically go.

Modeling the Battlefield

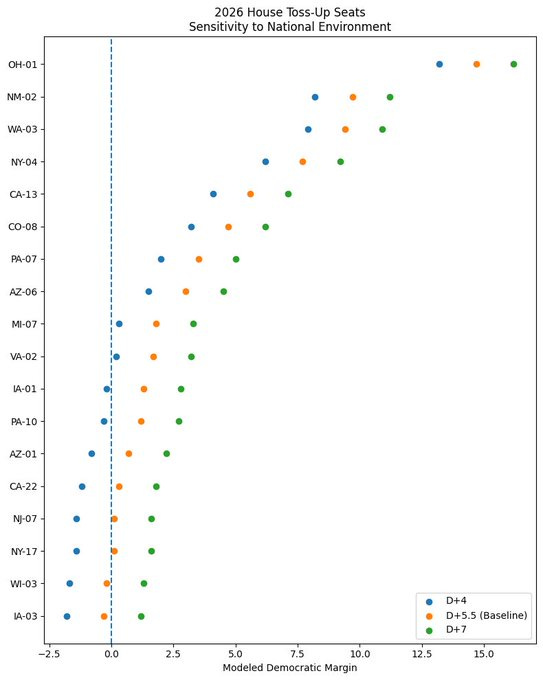

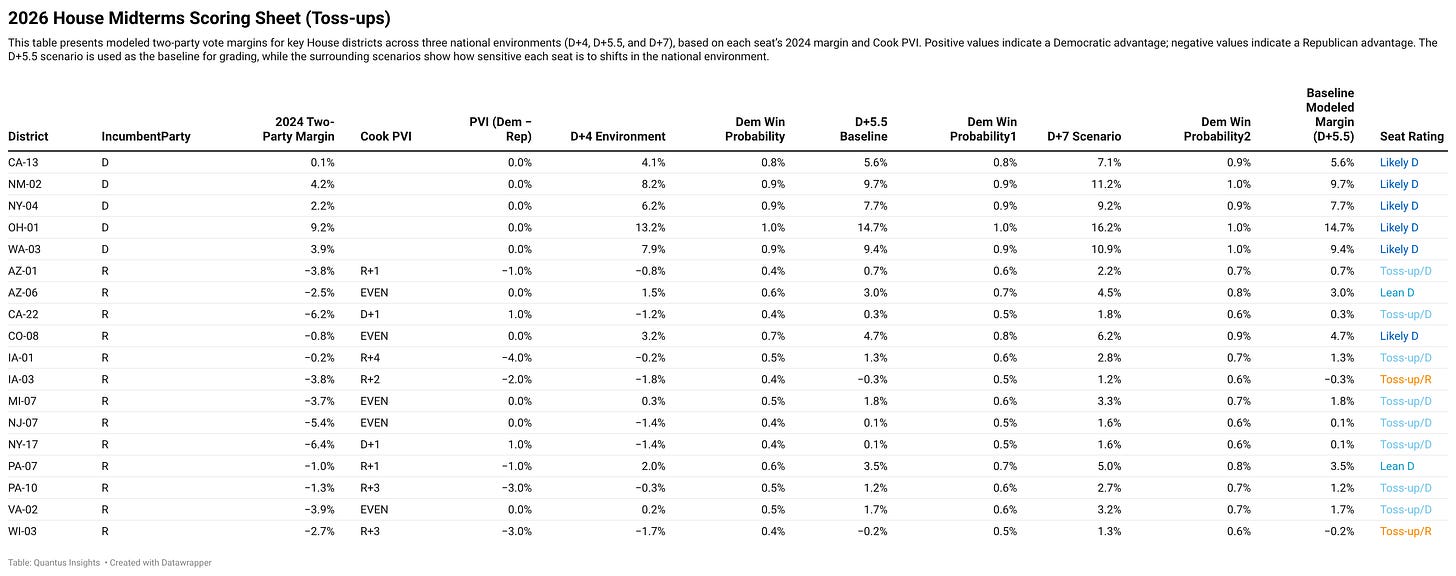

To address scale, we modeled the 2026 House battlefield using 2024 margins combined with Cook PVI, then stress-tested those seats under D+4, D+5.5, and D+7 national environments.

Each seat is represented by a dot. When its modeled margin crosses zero, the seat flips. Mapping these shifts produces a clear flip order and sensitivity ladder.

The results are instructive:

Republicans are vulnerable in the toss-ups.

Democrats have clear pickup opportunities.

But the map imposes a hard ceiling on gains.

Even as the national environment improves for Democrats, the number of seats that can realistically flip remains limited.

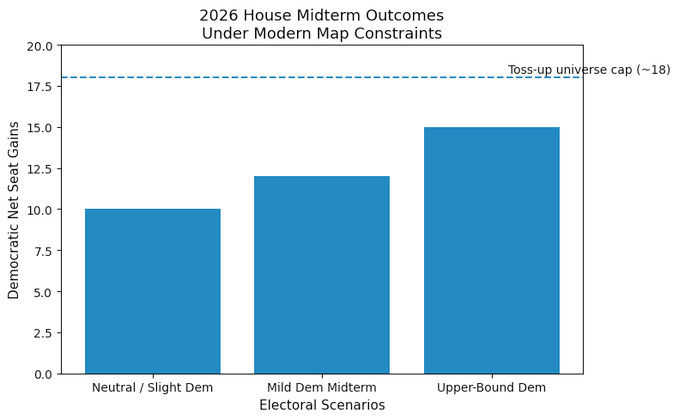

Three Plausible Outcomes

Overlaying all models: PEM, fundamentals, battlefield mechanics, and reduced elasticity, yields three realistic scenarios:

Neutral / Slight Democratic Environment

Democrats win ~10 of 18 toss-ups

Mild Democratic Midterm

Democrats win ~12 of 18 toss-ups

Upper-Bound Democratic Outcome

Democrats win ~15 of 18 toss-ups

Possibly all 18

Taken together, this places 2026 squarely in what can fairly be described as a “limited loss” environment.

While a loss of 11–18 seats would flip control of the House, it would remain modest by historical standards when compared to true wave elections like 1994 (−52), 2010 (−63), or 2018 (−41). That said, winning 15 of 18 toss-ups—an 83% success rate—would still qualify as a washout within the competitive universe. Scale matters relative to opportunity.

Tail Risk and Its Limits

If national sentiment were to turn decisively against President Trump and Republicans, tail risk does exist. But “wave” must be understood in context.

Republicans are defending just 218 seats, with limited exposure and a map dominated by structurally safe districts. For Democrats to approach a historically average governing majority—say, ~230 seats—they would need to sweep all toss-ups and win an additional 5–6 reach seats. Those conditions do not currently exist.

Only if voter behavior ceases to behave linearly, through turnout surges or backlash amplification, does that upper tail begin to open.

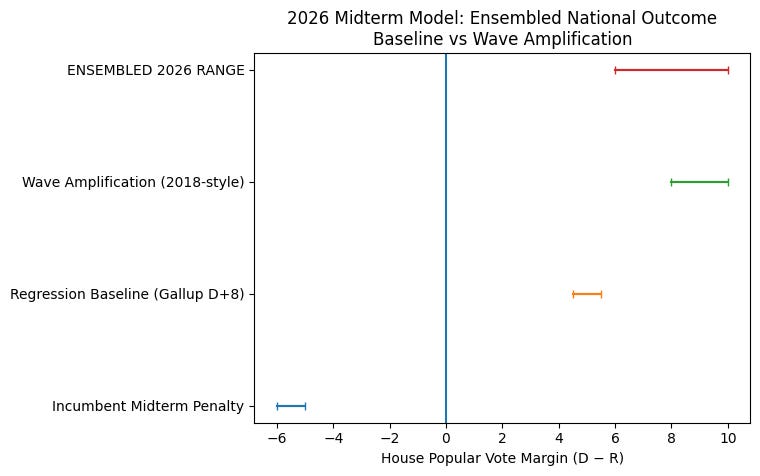

What Gallup Adds

Gallup’s party identification data helps clarify how much loss is plausible, not whether it occurs.

Restricting the analysis to modern midterms (2006–2022) shows:

The incumbent party always loses the House popular vote

The average loss is ~5–6 points

Gallup’s leaned party ID margin explains roughly 75% of the variation in that outcome

Today, Gallup shows a D+8 environment among leaned identifiers, a configuration that historically resembles 2006 or 2018 more than 2022.

A simple regression suggests a baseline House popular vote around D+4 to D+5. But history shows that once Gallup crosses D+5, outcomes often stop behaving linearly. In true wave midterms, turnout and backlash amplify results beyond the regression line: 2018 being the clearest example.

Using an ensembled approach that blends:

The structural midterm penalty

The current Gallup environment

And nearest historical analogs

The most reasonable projection at this stage is a Democratic House popular vote margin in the D+6 with possible amplification as high as a D+10 range.

That is not destiny. But it is no longer noise.

Conclusion

PEM is correct to flag a Tier 3, “prepare for losses” environment. The data supports it. But those losses are bounded by what is structurally possible in this cycle.

Even a wave-like result in 2026 would follow the same mechanics as past midterms, only at a smaller scale, reflecting the rigidity of the modern House map.

Direction is clear. Scale is constrained. And the outcome, whatever it is, will land closer to the floor than the abyss.