Pew Joins the Correction: Why Weighting by Past Vote Can’t Be Optional

How Pew’s methodological shift confirms the structural polling failure we exposed and why past vote weighting is now a civic necessity, not a technical debate.

This week, Pew Research Center made one of the most consequential methodological shifts in its history: it will now weight its surveys to reflect respondents' past presidential vote. To many in the polling establishment, this may seem like a cautious tweak. But to those who have watched U.S. public opinion research disintegrate over the past decade, it marks a long-overdue recognition of structural bias and a quiet validation of what firms like Quantus Insights have been advocating for all along.

Pew’s move is based on a simple, empirically grounded reality: certain segments of the electorate, especially Trump-leaning, non-college, and internet-skeptical voters have become systematically underrepresented in polling data. This is not a blip. It is a structural failure. And fixing it requires more than demographic weights. It requires reconstructing who we think the "average voter" actually is.

The Structural Gap Pew Just Acknowledged

In 2016, 2020, and 2024, major polls consistently overstated Democratic support. They were not just off; they were directionally wrong. The problem wasn’t late deciders or bad Likely Voter screens. It was nonresponse bias: entire segments of the electorate simply refused to participate in surveys, and pollsters had no way of accounting for them.

As we wrote in The Polling Crisis: Accuracy, Bias, and Reform in U.S. Political Surveys (2000–2024), "Polling continues to model the electorate it expects or prefers to see, rather than the one that actually turns out to vote." This failure is not random. It is patterned, persistent, and damaging to public trust.

What Pew has now formally acknowledged is that party ID alone cannot correct this distortion. Voters' behavior—specifically, how they actually voted—is a far more stable and revealing benchmark for ensuring representative samples. In fact, Pew's internal data shows that the effect of past vote weighting is modest (generally under 1 point), but crucial: it corrects consistent underrepresentation of Republicans and voters experiencing economic strain.

Why This Matters: Simulation vs. Measurement

For the past decade, polling has increasingly functioned not as a measurement tool but as a simulation engine: projecting elite expectations onto an electorate that doesn't quite exist. Forecasting models, media narratives, and campaign strategies have all been built on data that excluded key voter segments, not by accident, but by design.

As we warned, "Polling no longer measures the electorate—it simulates a cooperative, trusting subset, excluding rural, working-class, skeptical voters." And when those voters are disproportionately conservative, the simulation turns into bias.

Weighting by past vote is a corrective measure, not a magic bullet. But it’s a critical step toward rebuilding polling as a representational tool rather than a consensus simulation. As we've argued since launching Quantus Insights, this shift is not just technical. It is epistemological. We are not asking who responds. We are asking who counts.

The Data Speaks: Pew's Own Findings

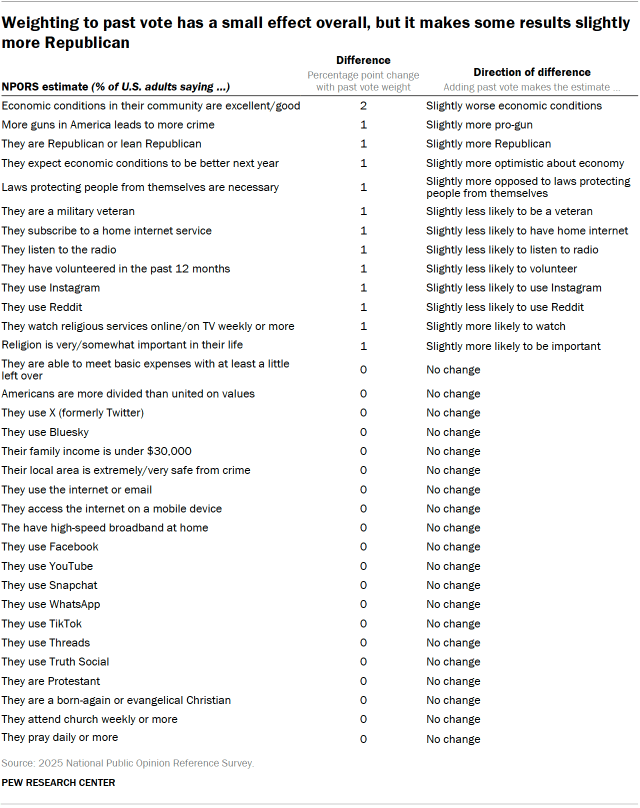

Pew's 2025 NPORS results show that weighting by past vote moved most results by 0–1 points. But those tiny shifts mattered:

More respondents identified as Republican or pro-gun

More expressed economic pessimism or hardship

Fewer reported internet usage, volunteering, or institutional engagement

In other words, past vote weighting brought hidden voters into the light and adjusted the story accordingly.

This echoes what we documented in 2024 when our own behavioral turnout model flagged late-cycle Republican enthusiasm that most polls missed. Our framework didn’t simulate engagement. It measured it.

A Quiet Vindication

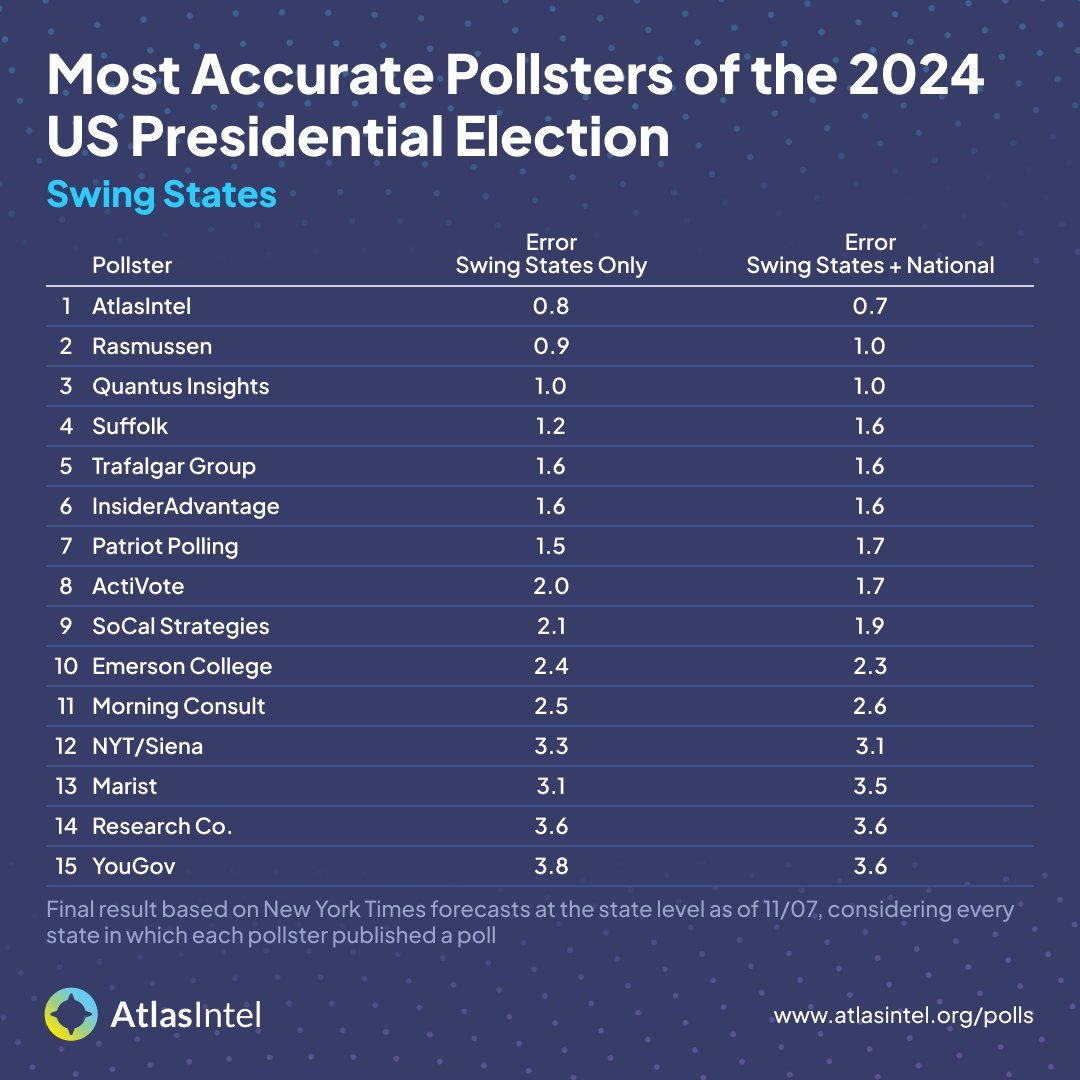

In April 2025, we published The Polling Crisis, documenting how structural bias and industry gatekeeping corrupted public measurement. We outlined how our own models, built with behavioral priors and past vote calibration, achieved record-low error in 2024.

In contrast to legacy pollsters who “smoothed over systemic bias with dense simulations,” our five-model framework surfaced reality from below. As we argued, “accuracy was not luck. It was structure.”

Pew's shift confirms what we've said all along: polling isn’t broken because it lacks math. It’s broken because it misrepresents who the electorate really is.

As we wrote then: "If polling can no longer be trusted to observe the electorate, the question becomes existential: What replaces it? The answer isn’t minor adjustment—it’s structural reinvention."

The Path Forward

We welcome Pew's decision. It will not fix polling overnight, but it is a meaningful step toward structural reform. If America's polling institutions want to recover their civic function, they must confront the uncomfortable truth:

Accuracy in public opinion research begins by acknowledging who isn’t showing up. And weighting by past vote is one way to make sure they still count.